Maria Reiche was born on the 15th of May 1903 in the historic city of Dresden, the German center of art and culture known as the “Florence of the Elbe”. Maria’s father, Max Felix, was a judge and her mother, Elizabeth, or Elli, as she was fondly called, had studied in both Hamburg and Edinburgh. In 1906, Maria’s younger sister Renate was born, and three years later, their brother Franz.

The Reiche home was a fine house in the old city, with vines and flowers filling the garden, but life for the three young children was strict, even cold. As Maria grew, however, she came to understand her father. They would walk together, often silently, in the woods of Saxony, each with their thoughts. She could have been set for a pampered life surrounded with the trappings of a classical education. She was eight in 1911 when the first performance of Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier was performed in Dresden, and the family thrived on music and the theatre. Indeed, Shakespeare remained one of Maria’s greatest pleasures. She also mastered English and French, which she spoke with easy fluency.

Looking back to her formative years of family and student days, Maria once said that her spirit of adventure must have been touched with a personal rebellion. Behind all her successes, her sister Renate made the running. Renate excelled at sports and pushed Maria to try harder, and it was Renate who persuaded her to accept with determination the prejudice which has dominated her life. But above all, Maria’s defined inquisitiveness surfaced. She was a dedicated mathematician and thrived on problems of logic.

When in 1926 the Nazca lines were first discovered, Maria Reiche was twenty-three and a student of mathematics at Hamburg University. Like many of her friends, she was aware of the political maelstrom enveloping post-war Germany where Adolf Hitler had just published Mein Kampf. Maria, on remembering these times, insists she was not a political animal. “In fact, I felt disgusted at the thought of all the hatred being generated and I wanted to distance myself.” Yet, like so many young people of the day, perhaps out of curiosity, Maria found herself drawn into discussions and noisy student meetings. Being athletic, enjoying swimming, diving and other sports, in the eyes of some she could be seen as the archetypal Hitler Youth. But while the National Socialists swept forward in the polls, eventually commanding six and a half million votes in 1932, Maria became even more determined to leave her country.

First Journey to Peru

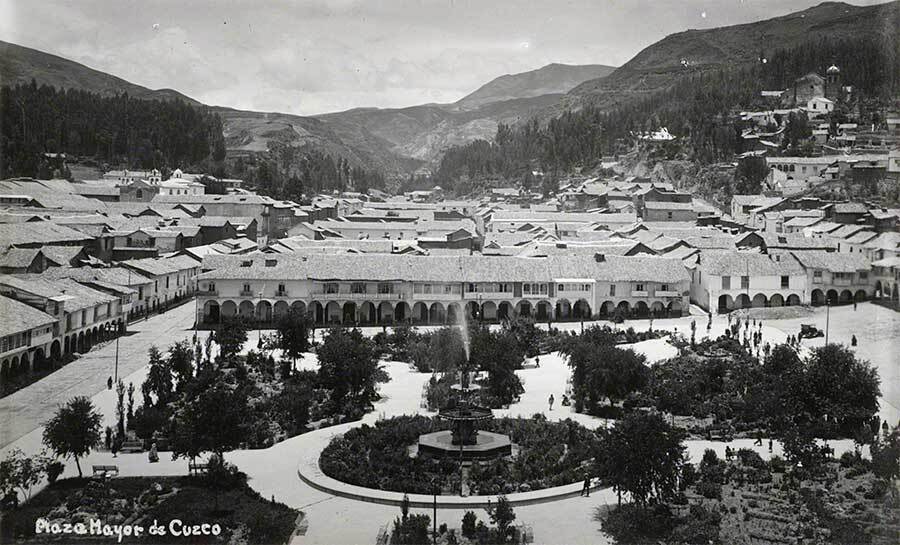

It was her love of children which drew her attention to an advertisement in a Hamburg newspaper which offered the post of child caretaker in the home of the German Consul in Cuzco, a Peruvian mountain city, once the famous Inca capital. Her application was accepted and, without a second thought, she set out alone on a five-week sea journey to the southern Peruvian port of Mollendo.

Maria has always insisted she was not fleeing the attentions of some student Romeo, though she has often remarked on her thoughts of marriage in those early days, saying how she felt love many times but “I never considered marrying a German; for me I wanted to make a one hundred percent successful marriage if I made one at all”. Her instinct was leading her, and she has never had any regrets.

Part of Maria’s interest in South America was her growing enthusiasm for astronomy, and she knew the work of the German astronomer Rolf Muller. In 1929 he published in Potsdam details of how certain Inca buildings in Cuzco had been built to face the rising sun at the important June solstice of the Inca calendar.

Much of this rich symbolism was still surviving when Maria reached South America, so there was more than enough to see and learn to keep her interest buoyed up. Her thoughts were never more positive than during the long train journey she made across the mountains from Mollendo to Cuzco.

Maria has always said that she believes her days in Peru were predestined. “It is difficult to explain, but you know when it happens. For me, Cuzco was simply the first step.”

She settled quickly into her new life, caring for seven-year-old Erhard and the delightful four-year-old Hilda, the children of Herr Tabel and his wife. Herr Tabel, besides being the German Consul, was also the director of the Cuzco brewery.

Although the Inca foundation of Cuzco dates from AD 1200, at which time many of Europe’s cathedrals were already old, the open squares and narrow streets possessed the qualities of a time capsule. All the sights, sounds and smells of this city transport a visitor back into the Middle Ages in reasonable comfort.

Maria Reiche looked at this scene and was fascinated by the customs of the people, who are barely a few steps removed from their ancestry. But as a child caretaker, she had little time to pursue her personal ambitions. Fortunately, the thing she enjoyed most of all in her work were long walks or outings in the children’s company. They were taken by Herr Tabel’s chauffeur to places in the mountains like Tambo Machay, the remains of an Inca hunting lodge.

Of the many facets of the new world around her, Maria understood the ways of the Indians and their belief in ancient gods. The Spanish invaders had stamped on the old customs and tried, though not always successfully, to superimpose a Catholicism which was seen by Maria through the eyes of the strictly conventional Cuzco families.

It was after one of her trips into the Andean countryside that Maria found a splinter deep under the nail of a finger on her left hand. A severe infection followed and at the insistence of her employer, she braved a Cuzco hospital and surgery for the removal of the tip of the finger. One of her old friends later remembered how Maria described the remarkable vision she experienced while under the anesthetic. Apparently, during the operation, she seemed to leave her own body and, floating out of the window, had seen all of Cuzco spread out below. As she came out of the anesthetic, she realized she was returning to her own body.

But her job was not to last. Maria and the Tabels never saw eye to eye. Although the children were her joy and she loved them dearly, when eventually they distanced themselves from their parents, her contract was quickly ended. The year was 1934, and she found herself bundled on a train with her luggage bound once again for Mollendo, where her ex-employer ensured she boarded a ship bound for Lima and Germany. Maria, however, was determined to stay in Peru.

When the ship berthed at Callao, the port for Lima, she was told her papers were not in order and was refused permission to go ashore. Here again, Maria believes that predestination played a part: during the voyage she had made friends with a lady who not only had the right connections, but also tempted her to open a kindergarten in Peru. Maria accepted the challenge and immediately all the formalities were waived.

She spent much of the next few months in Ancon, a small coastal resort surrounded by desert and about 40 kilometers (25 miles) north of Lima. It was a pretty town of palms and large avenues of South American pine trees and Maria spent much of her time wandering amongst the desert hills where there is nothing but sand, nothing alive, no plants, no birds, no sound - nothing but an immense silence and solitude.

Returning to Germany

The kindergarten started and almost as quickly closed, and once again Maria found herself without a job or permission to stay in Peru. She freelanced for a short while and then, in 1936, returned to Germany to stay with her mother in Hamburg.

The visit was brief. Maria lectured briefly on her travels at the Völkerkunde Museum, and then at a clinic in Halle, where Renate, her sister, was working. By 1937, less than a year since leaving Peru, Maria was once more on a ship bound for South America and Lima.

Second Journey to Peru

Maria was living in a small, rented apartment close to the city center, giving lessons in mathematics and gymnastics three times a week at the English school. Once more, she found she developed a strong rapport with the children and this time; it ensured her job. As she made friends in the pre-war Lima, Maria found herself drawn increasingly into intellectual and cultural circles.

By 1938 she was working in the National Museum, translating German scientific and technical journals. Another part of her work was the supervision of the restoration and repair of the beautiful cloths which wrapped the bodies of ancient Peruvians buried some two thousand years ago. These mummy wrappings were discovered in simple tombs beneath the sands of Paracas, a desert peninsular roughly halfway between Lima and Nazca.

The Paracas site was excavated by the Peruvian expert in archaeology Julio C. Tello and Toribio Mejia, Tello’s principal collaborator when the work began in 1925. The excavations continued until 1930, during which time Tello and Mejia discovered that some of the perfectly preserved mummies were wrapped in embroidered cloths of unrivalled quality.

Maria’s work for Tello provided her with a small income and valuable experience. Though Nazca and its strange markings had yet to make its mark on her, the mystery that eventually took over her life was getting closer.

In the 1930s, flights across the desert became more common. One pioneer airline, started by the American Elmer J. Faucett, had stopping places on its route southwards to Arequipa. As pilots flew from Palpa to Nazca, a distance of about 65 kilometers (40 miles), they realized that the desert was covered with many geometric shapes. As the first aerial photographs were taken slowly, the lines became known. The British ethnographer and archaeologist, Geoffrey Bushnell, flew over the lines in 1939 and fifteen years later, as Curator of the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, he said “Whatever the explanation, the setting out and execution of these perfectly straight lines and other figures must have required a great deal of skill and disciplined labor”.

But in 1939 the lines were only a curiosity. Though the shapes and straight lines were being classified by Toribio Mejia, urged on by Tello, they were very much an afterthought to his work. Mejia had made a special trip to Nazca to draw some lines and planned to announce his work on this project at an International Congress in Lima, to which they had invited experts from all over the world. While Maria was working with Tello, he had introduced her to many archaeologists who were preparing their work for the Congress.

The Teashop

As the date of the Congress approached, Maria made friends with Amy Meredith, an English lady some twelve years older. Amy, who owned a small teashop in the center of the city, had both charm and an energetic personality. Maria and Amy became brilliant companions, spending much time together and always enlarging their circle of friends. Often Maria helped Amy in her teashop, which had become a well-known gathering place for transient foreigners, as the teashop, in a narrow passage near the Plaza de Armas (the main square), was well placed to catch travelers, sightseers and shoppers.

Paul Kosok

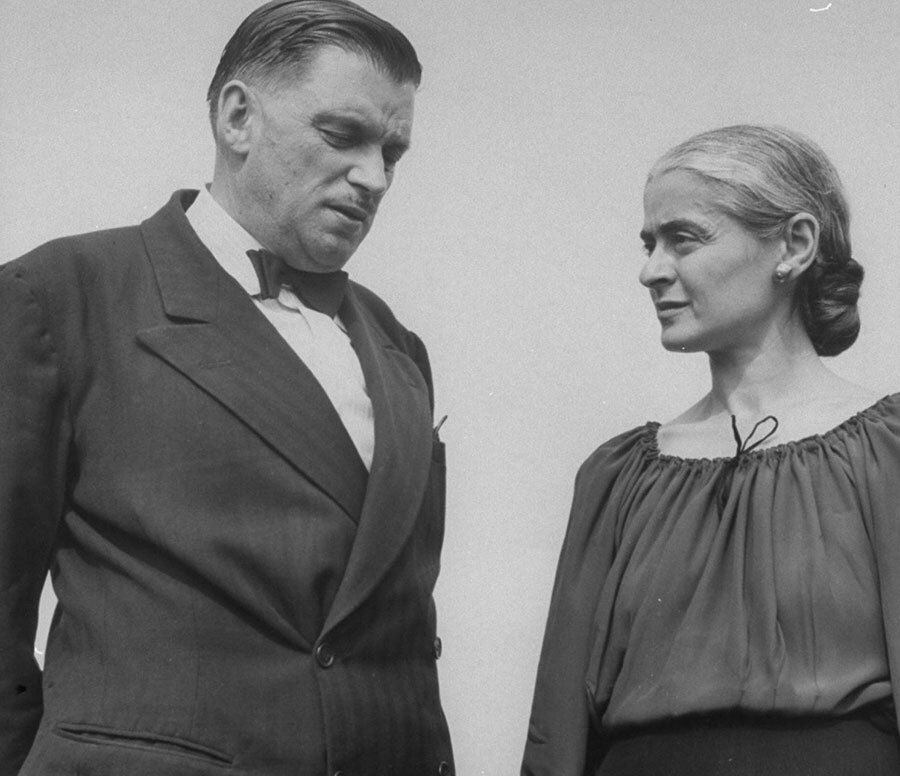

Paul Kosok, a well-built native New Yorker from Long Island University, was just one of many who visited the teashop, where his enthusiasm caught the attention of Maria and Amy. Twice married, Kosok travelled to Peru in 1939 with his second wife, Rose Wyler. He had joined Long Island University ten years earlier as an instructor specializing in history. The trip to Peru was intentionally brief; more of a preliminary survey of the ground he intended to cover in a proposed study of early irrigation methods. Kosok then returned to the United States to present his work to a congress in Washington in 1940. Later the same year, he took a year’s leave of absence from the university and returned to Peru with Rose.

Most of his work was focused north of Lima, where the remains of pyramids, fortresses, canals and settlements rest among sprawling fields of sugar cane. But Lima offered museums and libraries and Maria Reiche found herself once more employed as a translator, this time for Kosok. It was early in 1941 that he traveled to Nazca. Toribio Mejia’s account of the lines and the possibility that they were connected with irrigation was sufficient to persuade him. He arrived with Rose in the Nazca desert in June.

For reasons which are not clear, Kosok worked on the desert pampas a few kilometers (miles) to the south of Palpa. One traveler who knew this place from as far back as 1929 was Duncan Masson. He had passed through the desert, crossing the lines, and some years before he died, he recalled the experience: “As we drove over the pampa, we saw these trenches to the left and right of the track. They were obvious and you could not miss them. It was this place where Kosok headed initially and, sure enough, to the left of the road he found a perfectly straight line leading to a hill almost 3 kilometers (2 miles) away. On the other side of the road, the line continued across the desert to the foot of another range.

Paul Kosok turned to the first hill and found that it was the center of a complex of lines. Some narrow, others over 3 meters (10 feet) wide. Some lines led to the crest of the hill, their form being clear as shallow U-shaped trenches. At the top, overlooking the desert, Kosok found piles of stones at the ends of the lines and a large area cleared of surface stones. The clearing followed the form of the hill, though with a clearly defined trapezoid outline.

The conditions in the desert were not good. Kosok and his wife had to carry everything they needed for the day’s work, including drinking water. But as they traced the form of the trapezoid, they realized that one end was embroidered with a complex design of finger-like projections. The pattern was scraped in the ground, though to a lesser depth than the main shape of the clearing. This was the first of the designs to be discovered and describing it, Kosok could offer no explanation: “What it portrays we do not know”.

It was on the same visit that Kosok noticed the sun setting almost directly at the end of a line, and understandably, he was struck with the thought that the remains could have had some astronomical or calendrical connections. These ideas were predominant in his mind as he headed back to Lima and Amy’s teashop.

Finally, Nazca

Once more among interested friends, he talked over his discoveries and ideas with Maria Reiche, who was captivated by his findings. Here was her subject: mathematics, with astronomy, time, calendars and her recent interest in archaeology all rolled into one. Kosok offered some small funds to Maria if she would continue the investigation after his return to the United States. She agreed. “Once more I knew it was my predestination at work”.

The next step involved more observations of the sun and Maria and Paul Kosok decided she had to go to Nazca and see that year’s December solstice, the time when the setting and rising sun reaches its extreme position on the north-south journey along the horizon. All the evidence up to that moment pointed, according to Kosok, to the lines being an ancient calendar. “It was”, he said, “the largest astronomy book in the world.”

Maria Reiche was thirty-nine when, late in 1941, she set out by bus for Nazca. In the 1940s, the bus could take as long as twelve hours to cover the 440 kilometers (275 miles). The service was reliable enough, though with frequent stops and moments of concern for the survival of machine and passengers. The rugged Andean foothills, a barren stony desert, and valleys filled with neat orange groves were Maria’s first taste of this part of Peru, and she immediately sensed it could be her next home.

But there were drawbacks, and the hotel in Nazca where she stayed, she remembers was a filthy and noisy dump. Nights in the Hotel Royal were so disturbed that, after a brief rest, Maria always left her room in the middle of the night to look for a passing truck to take her to the desert pampa for sunrise.

Following Paul Kosok’s suggestion, Maria began her investigation by looking for any lines laid towards the rising and setting points of the sun at its solstice. The time of year, midsummer in Peru, and a cloudless sky were, as Maria remembers, simply perfect on the 21st of December, and within the next few days she identified sixteen solstice lines. Once in the desert, Maria had no difficulty verifying Kosok’s original discovery relating lines to a solstice. For a few days on either side of the 21st of December, she saw the sun rising in the same place.

Kosok put two and two together in 1941 during his visit and suggested looking for moon lines, planet lines and star lines. By the time he had involved Maria, he had already hinted that some lines pointed to the Pleiades, a group of stars recognized through the ages. Although Maria easily identified lines which pointed in the right direction, she realized she faced an astronomical puzzle.

Apart from the laborious task of making her calculations by pencil and paper in the pre-calculator age, Maria had to consider other technical points such as the height of the stars above the horizon and the height of the horizon above the level of the pampa itself. Both these variables needed to go into her equation, or her research would be worthless. But on her first Nazca exploration, she simply did not have the financial resources or instruments. The Pleiades and all they stood for would have to wait until next time.

The Impact of World War II

By the end of 1941, Maria had finished her work in Nazca and returned to Lima to write to Paul Kosok. It was then that the full force of the war intervened and, with America involved, Kosok’s Nazca work came to a halt.

Mostly, Maria spent the war years in the company of British and American friends who offered her great kindness. For many years, she and Amy shared an apartment in Lima beside the Parque de la Reserva, close to the center of the old city. Although Maria continued to teach, she also took on the job of book-keeping for Amy’s growing business. All this activity kept her occupied and her mind off the problems of communication with her mother and sister Renate in Germany. Nazca, too, was temporarily retired.

In the three years since Maria had been forced to abandon her fieldwork, there had been changes in Nazca. An earthquake damaged much of the town in August 1942, reducing both the church and part of the original Hotel Royal to dust.

At about this time, the Peruvian Airforce and an independent air survey company were mapping parts of the desert using specialized photography. The enthusiastic response to the lines mystery by the staff of the National Air Photographic Service (SAN) has since become a vital part of the Nazca story.

Dr. Hans Horkheimer

Even before Maria had the chance to return to Nazca, Dr. Hans Horkheimer, a lecturer from Trujillo University in the north of Peru, examined the lines. Horkheimer was returning from Chile at the end of 1945 when he saw the lines from the aircraft and was immediately fascinated. He used part of his vacation for an excursion to Nazca and, through influential contacts, enlisted the help of the Peruvian Airforce. In February and March 1946, they gave Horkheimer three special flights over the desert and he completed two ground excursions.

Summing up, Hans Horkheimer favored a connection with the well- recognized ancestor worship of the ancient Peruvians. The cult of the dead and reverence for departed spirits remains strong in the Andes mountains to this day. He found many stone constructions among the markings which he believed were tombs, and he also noticed stones gathered in heaps - each formed with a central depression like earth ulcers. Horkheimer called them “stone discs”. These, he said, marked “sacred places before which the people made sacrifices, their pagan invocations and other ritual activities”.

Horkheimer returned to Trujillo, preparing to announce his discoveries and conclusions just as Maria was setting out to return to Nazca. A race to be first with the solution captured the imagination of the Peruvians, and the newspapers in Lima and Nazca were quick to report every fresh story and twist to the opposing theories.

Return to Nazca

Maria arrived in Nazca in June in time to watch the midwinter solstice. Maria could not afford to stay long in Nazca and, relying as she did on her meagre pay as a teacher and out-of-hours work for Amy, was forced to return to Lima.

The newspaper editors never failed to keep the Nazca story in front of their readers, and by 1947, Maria had made her name in Peru. She confided jokingly at a party in Lima: “I’m a celebrity now”, but outside Peru the story was different; the mystery of the desert markings still had to make an impact, and that fell largely into the hands of Paul Kosok, who was waiting in New York for funds to support further desert studies.

But international fame did not touch Maria, and she had to survive on a shoestring while somehow clinging to her place as the Nazca front runner. Time was on her side, and she had plenty of it to make excursions to the pampa. What she did not have was money, but the San Marcos University in Lima (the oldest in the Americas) promised a small grant and a theodolite. Eventually the San Marcos grant was arranged, the debts repaid, and the theodolite delivered. In Nazca, Maria was given the use of a truck owned by the town and gained the unreserved backing of a colonel from the Army Geographical Service on location there.

While on the surface her work progressed well, Maria was aware of criticism and sensed murmurs of disapproval. After all, she knew she was not an archaeologist, and she was getting a great deal of publicity. But she could not let such thoughts obstruct her progress and forged ahead. She did not stop even when, in early 1948, Amy took a brief trip to the Amazon jungle on the far side of the Andes mountains. But some months later, when Paul Kosok had still not arrived, her lack of money and failure to get the results she expected almost forced her to give up.

So, when eventually, after a seven-year absence, Paul Kosok arrived in Lima, Maria greeted him with mixed feelings. For all those years she had worked alone on the problem and suddenly here was Kosok, the originator of the astronomy theory, with all the international weight behind him. Now he could offer her expenses and take all the credit. But more than ever before, she did not want to give up her very private happiness on the pampa.

Maria told her friends that she would have to come to some agreement with Kosok; on the one hand, he had introduced her to the lines while she, on the other, was dedicating her life to the problem. Despite a certain tension between them, at least the lines of communication never broke down completely and Maria agreed to join Kosok in northern Peru the following year.

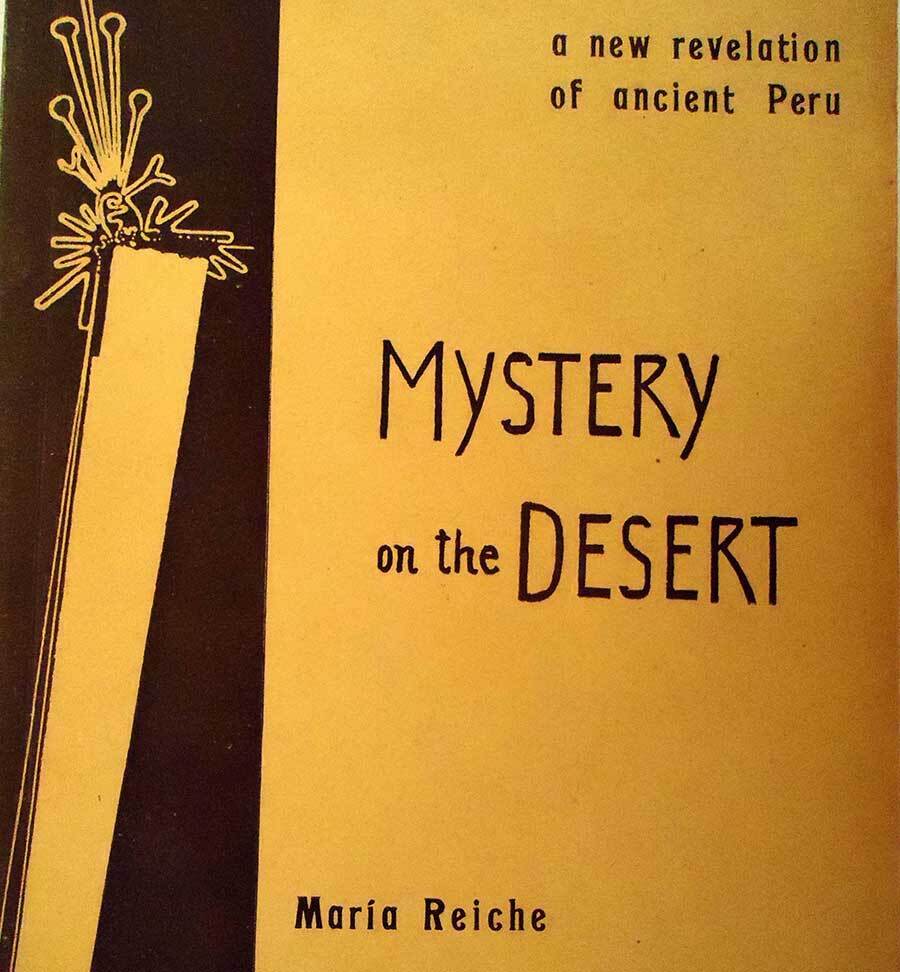

Meanwhile, Maria was working non-stop on her private project. For some time, she had been planning a small book she intended to publish in Spanish and English. She wanted this book to be the first, and thus potentially the most important account of the issues at Nazca. Both editions were to be illustrated with the latest photographs and her own unique maps.

Mystery on the Desert

With the success of her books, the 1940s finished well for Maria and she talked of a better, perhaps an international, edition of “Mystery on the Desert”. Kosok left Peru and Maria, who had assumed the character of a persistent student, returned to the desert. Early in 1950, she arrived at a settlement by the peaceful river of Ingenio, 24 kilometers (15 miles) from Nazca.

In February 1951, La Prensa, a Lima newspaper, reported that Maria was living in a small house in San Pablo and receiving a small amount of money from the United States to help with her work. The article said that her attention had turned towards the animal figures and an interpretation of their meaning.

When not in her desert hideaway at Ingenio, Maria continued to work for Amy in Lima, looking after the accounts of her expanding property business and teaching or translating in her spare moments. Otherwise, she was occupied with Nazca research.

She was in touch by letter with Rolf Muller, the astronomer who had studied the Cuzco temples, and she looked for academic funds from overseas to underwrite her scientific endeavors. But she found it to be the proverbial “chicken and egg” affair, with the academics needing more information than she could provide before they would promise support.

From 1952 to 1955 Maria continued to work on the pampa, breaking her studies only for quick visits to Lima where she kept a small, rented apartment. During her absences, Maria let her rooms to visitors and the money helped with the field expenses, so on her visits to Lima she sometimes stayed with friends.

Irrigating the Pampa

One afternoon early in August, she arrived in Ingenio by bus to find the pampa marked by long rows of wooden stakes. These had apparently been put there as markers by workmen who, with no care for the fragile desert surface, had rushed about in jeeps across the lines and figures. Car tracks and footprints were everywhere. When Maria asked the meaning of the sudden invasion, the storehouse caretaker simply replied, “the pampa is to be irrigated next year”. Maria was stunned, but not speechless. “They planned to irrigate 200 square kilometers (50,000 acres) and all the benefactors were tied to the Government - I knew I had to stop them”.

The Lima press and the Peruvian Airforce took up Maria’s cause. After her flight, Maria staged a massive Nazca exhibition with the Air Photographic Service (SAN) using some 800 photographs of the desert calendar as the markings were then called.

They fought much of the battle in the Lima press in September 1955 when landowners and politicians opposing the value of the desert markings and Maria’s work. Maria replied valiantly by attempting to explain the philosophical and practical complexities, the significance of straight lines, animal figures, the heavens and astronomy, all potent ideas in those early Pre-conservation days.

Many of her supporters could not understand her explanations, yet everyone on her side agreed on one point: the lines were mysterious and should be saved. They renewed an old proposal that they should create a national archaeological monument along the southern border of the Ingenio valley, the pampa of San Jose being cited as the most important place.

Maria tried to generate interest in the proposal in Germany and dispatched newspaper clippings and translations. Perhaps the German press might draw world attention to the need for a conservation plan. But such rearguard action proved unnecessary, as by the middle of September the controversy reached the Peruvian Chamber of Deputies. Several politicians, sensing they were losing popular support, changed sides to back Maria, cancelling the concession of the land developers and calling for the trial of the Director of Irrigation. Government officials visited Nazca on the 15th of September 1955 and they gave the order to suspend the work.

An impressive victory for Maria that slowly established her role as the primary protector of the Nazca Lines.

Success, Setback & Tragedy

Maria’s precise report of the “monkey” (Nazca Line) and her interpretation of its astronomy was published in Lima in 1958. During 1959, both El Comercio and La Prensa continued to support Maria. Jorge Recarraven, a locally famous correspondent, writing in La Prensa, recalled Maria’s love of Peru, saying she was a great “Peruvian”, and the paper’s cartoonist portrayed her with an already deeply lined and serious face.

But less than three weeks later The New York Times gave another story: “Lima, Peru, 20 June: Tracings in Peru Called a Calendar - a woman’s view on drawings of ancient Indians is disputed by many”. Far from supporting Maria’s view that the lines represented a vast astronomical observatory and calendar, the Lima correspondent of the newspaper claimed that many archaeologists here are reluctant to accept this interpretation. After so many years of work, it was a bitter blow.

To make matters worse, news reached Lima of Paul Kosok’s sudden death. He had been in a nervous and agitated state for some time before he died, and Maria realized his book was unfinished and some way from publication, so the future of Nazca could be in her hands.

But at what cost? Her health was suffering and the pampa she loved was under attack. Then, as summer approached, Amy’s condition worsened. The two ladies travelled briefly to Ingenio, where Maria hoped the climate would be good for her old friend, but there was no chance. The cancer had gone too far. Amy returned to Lima for the last time and died with Maria by her side. Amy’s struggle had been courageous and through even the darkest moments, she was persuading Maria to write the book of the lines. Maria, then almost sixty, promised to complete the story.

By the mid-1960s, Maria was making progress with her analysis and preparing to publish again. She settled into her Lima apartment, travelling frequently to Nazca. In 1965, she wrote two articles for Lima magazines.

Two-year Break in Germany

Then, in a most extraordinary way, events moved positively for Maria. They offered her funds to produce a new book about the lines. The Corporation for the Reconstruction and Development of Ica would pay the printing costs in Germany and Maria’s fare. Maria saw the chance to present her work in Germany and try for a doctorate from Hamburg. Again, the “Gods of Nazca” were on her side and at last she could show the world what Nazca really meant. It was the opportunity of her lifetime. She set out for Germany in June 1967 after another tiring journey to the pampa.

Maria’s two-year break in Germany was time well spent. In 1968 she published her new book, also titled “Mystery on the Desert, which was given a foreword by Professor Trimborn from Bonn, thanking her for her tireless work. She renewed her contact with the German press and Frankfurter Allgemeine described the book as an editorial sensation.

Towards the end of her stay, Maria briefly visited England to see stone circles and talk with Professor Alexander Thom, the acknowledged expert on ancient measurement units. In May 1969, she lectured to a small audience at the University of London. Then, her travelling over, she returned to Peru.

In Lima, she moved back to the San Pablo storehouse. “There is nothing to keep me in Lima”, she said. The city had grown beyond recognition to a vast sprawl of two million, mostly poor Indians from the mountains.

Chariots of the Gods - Erich von Däniken

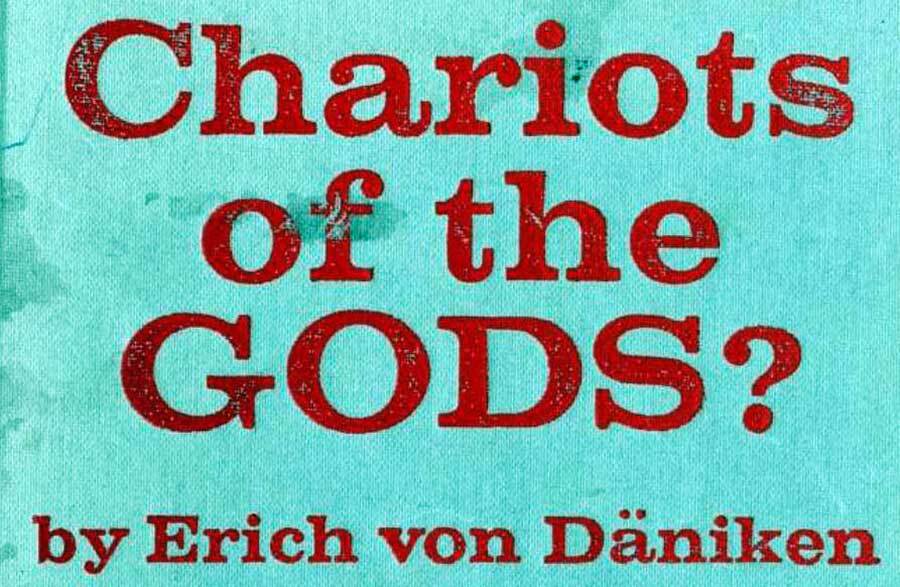

But Nazca, too, was changing and following the publicity the first groups of tourists arrived. But Maria was about to face a problem which overshadowed all other worries. The imaginations of millions of people worldwide were caught by the idea that the Nazca lines had been built as runways for ancient astronauts.

Erich von Däniken, a Swiss hotelier turned writer, launched his best-selling speculation on the world in 1968. Within months, he published the book in a dozen countries. “What is wrong with the idea”, von Däniken asked, “that the lines were laid out to say to the gods: Land here?” While archaeologists shuddered at what they felt was professional blasphemy, the paperback editions of “Chariots of the Gods” poured from the presses.

So, at the beginning of the 1970s, travelers young and old with a copy of von Däniken's book in their hands were streaming across the desert looking for a spacecraft. Cars, motorbikes, trekkers with donkeys, even artists who made their own figures to be seen by the gods - all were scuffing the fragile desert. Maria complaint that a pilot had actually landed on one of the “runways” and diminished into insignificance. “The pampa will be destroyed”, she declared to everyone who cared to listen and, aged sixty-seven, she took up the fight where she left it fifteen years earlier.

Initially, Maria’s sympathies lay with von Däniken and his disciples as they reached out for strange culture heroes. But then, as crowds scrambled over the pampa, her sympathy was put under intense pressure, and she became enraged by the uncontrolled, thoughtless destruction.

More Threats

Maria also complained about the increasing local pollution. Worst of all, the pollutants, according to her, are the fallout of dust from the extensive Marcona mine in the desert some 40 kilometers (25 miles) south of Nazca. Open-pit mining, which began at Marcona with American finance in the 1950s, depends on daily quarrying with explosives. Maria believed that its fine dust carried skywards by the blasts settled on the pampa and discolored the stones.

It was hard for Maria to accept, but Nazca was remote and something of a curiosity. She was too close to her subject and, while she understood it well, it baffled most of her readers. When faced with outsiders disbelief of the critical situation, or the sheer institutional disinterest, her reaction was to strike out alone.

The key, Maria explained, “is to give the tourists something to see - you have to be above the lines, and people coming here for the first time do not realize that. All they do is walk around in circles looking, marking the desert and discovering their own footprints.”

The Viewing Tower – “El Mirador”

In 1974 Maria worked towards building a sixty feet high viewing tower, set near the road. From the top platform there would be a panoramic view which she said “must be free of charge. Otherwise, no one will use it”. For funds, Maria turned to friendly companies in Lima, to Renate (her sister in Germany) and to sales of her book “Mystery on the Desert”. By Maria’s contract with the Corporation for Reconstruction and Development of lca, the money from sales belonged to her. After travelling once again back to Germany, she raised the needed funds, and she completed the tower: “El Mirador”.

The loneliness of the pampa had vanished. Tourists were climbing up the view tower and light aircraft made half hourly sorties over the monkey. Maria became the star of Nazca, but she saw the attention with mixed feelings and was only happy when she saw the pampa empty, often complaining that all these visitors could ruin it in a few weeks.

Her travelling, the years of poor diet and her growing concern about polluted food had left her tired. She was in her seventy-fourth year and, since the end of World War II, she had thrown herself almost non-stop into solving the desert mystery. Her effort did not go unnoticed in Nazca, which was enjoying the benefits of expanding tourism. Her impact and determination were so strong that in late 1977, the Peruvian Government honored her with “The Order of Merit for Distinguished Services”.

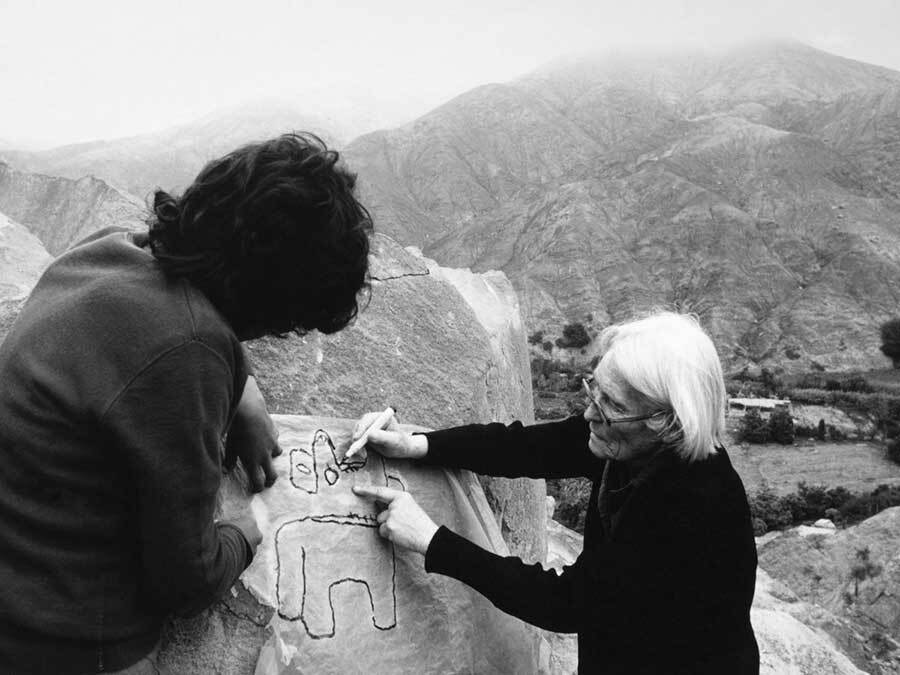

Towards the end of the 1970s, the momentum at Nazca changed again. The lines were now an established tourist attraction and Maria, approaching eighty, was kept busy. Guards had to be found - and paid. Tourists and reporters always needed her views. Her work on the pampa continued, often with the aid of assistants and students. Maria admitted privately that she was tiring and looking for someone to take over the work. “But it has to be a person who is prepared to live here and not just stay a few days. The pampa needs patience”.

Deteriorating Health

Such a person was hard to find so, despite deteriorating eyesight because of glaucoma, Maria determined to continue alone. She was comfortable in the hotel and respected by the people of Nazca. After almost forty years, the Doctora Maria Reiche had become one of them and put their town on the map.

When asked if she will author her own story, Maria usually responds, rather shyly. “No publisher would dare publish what I have to say!” Or she simply passes over the idea with an ironic comment about “after I’m ninety”. When a French television producer created a film based on her life and applauded her as “The Lady of Nazca”, the fame led a reporter to announce her death. But Maria Reiche was not ready to join the Nazca spirits. “I had to write to the publishers and tell them I was still alive. How stupid!” She still laughs at the joke.

By her eighty-first birthday, Maria Reiche had developed her new theory still further, and they announced it in “The Lima Times”, the successor to “The Peruvian Times”. Interviewed by senior reporter Vanessa Baird, Maria said she had made a crucial new finding. The circumferences of the figures represent exact time spans - the “bean sprout” is exactly a calendar month, and another drawing, the “key” on the pampa near to the humming-bird, is 365 days, exactly a year”.

Knowing her sister’s determination to continue her work, Renate, who had retired from her medical practice, spent more time in Nazca where she could supervise Maria, who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Maria was insistent on using local herb remedies and, as Renate had specialized in homeopathy, she treated Maria following this system. By the end of 1984, the disease was coming under control and Maria continued with a heavy workload of interviews, lectures to hotel guests and flying over the pampa whenever she had time.

But her eyesight problems plagued her work, and early in 1985 she travelled to the United States for consultations, where specialists at the Bascombe Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, offered free treatment in recognition of her work at Nazca. By then, Maria had received more honors and awards in Peru, including the Congress Medal of Honor. Much to the concern of everyone who knew of her dedication to Peru and the mystery of the lines, the prognosis for her eyesight was bad: the specialist had said her eyes could not be improved. “I will have to accept it”, she said calmly. “I should have taken more care in those early years on the desert.”

In the wake of world-wide publicity on the lines, Nazca was changing. The Tourist Hotel, Maria’s home, was enlarged and modernized. Restaurants and bars opened literally overnight.

At the end of 1985, she fell and broke a hip, which recovered well after treatment in Lima. Despite press reports of blindness, she could still see, though faintly, and as ever she returned to her work protecting the pampa. The “Doctora” continued with press interviews, and the daily lectures in the hotel took much of her time. Television stations booked time with her through her sister Renate. In March 1987 National Geographic Explorer visited her, with photographer Marilyn Bridges, archaeologist Helaine Silverman and Phyllis Pitluga. “It was an all-women event”, said Renate, “and the next will be with the Canadian television”.

Spare moments are exceedingly rare for Maria, but somehow, she makes time to continue perfecting the measurement unit, remaining convinced that the answer to the mystery will be found. But she is emphatic: “You must know the pampa and the people. Even today, you will find parts of the desert where Indians will not walk. They say such places are full of evil spirits. To you and me, it may be as simple as a spot where a shadow touches a track. Have you not walked down a path and avoided stepping on the lines where paving stones meet?” Maria vividly recollects where certain lines change direction in the shadow of a hill. Such places are still sacred in parts of the Andes and are usually marked with stones.

Final Years

All her years of experience have yet to be written. “There are special places you find only when you live on the pampa. Some people here know about them, but they are very secret”. And when asked for a precise spot, Maria Reiche’s face gleams with vivid memories of her solitary explorations as she leans forward to whisper: “It’s close to the… No. Wait! I’ll put it in my next book”.

Despite her age, Maria continued at an unbelievable pace to take care and protect her “secret places”. Her health continued to deteriorate: she lost her sight completely, suffered from skin diseases and finally was restricted to a wheelchair. On the 12th of July 1995, her sister Renate died unexpectedly from health complications. Aged ninety-five, Maria Reiche died of ovarian cancer on the 8th of June 1998 at the Fuerza Aérea del Perú (Peruvian Air Force) Hospital, at the Las Palmas Air Base in Santiago de Surco, Lima, Peru. They placed Maria to rest next to her sister in El Ingenio (Ica) - near Nazca at the house she had lived under such poor conditions for so many years.

In honor of “La Dama de Nazca” (The Lady of Nazca), the house was converted into a small museum: Casa Museo María Reiche (Maria Reiche House Museum), Km 421, Carretera Panamericana Sur, El Ingenio, Provincia de Nazca, Ica, 11350 Peru

Notes

Reiche’s immense dedication deeply endeared her to the people of Peru, so much that in 1992 she was granted Peruvian citizenship, and the Nazca airport is named after her. In 1995 the UNESCO declared the Nazca Lines a World Heritage Site.

Google Doodle celebrating Maria Reiche’s Birthday

On the 15th of May 2018 Maria Reiche’s 115th Birthday was honored with a Google Doodle by Guille Comin and Elda Broglio depicting the “Lady of the Lines” in her element:

“As the sun peeks over the high desert horizon in southern Peru, it illuminates a rust-colored blackboard scrawled with curious white lines - some perfectly straight, many with hairpin curves - that stretch for miles. Only from the air are the subjects revealed: a monkey, a spider, a hummingbird, and many more. These are the Nazca Lines, and for decades, Maria Reiche was their staunch guardian - a lone woman perched on a stepladder, bearing a sextant, compass, broom, and mathematical mind.”