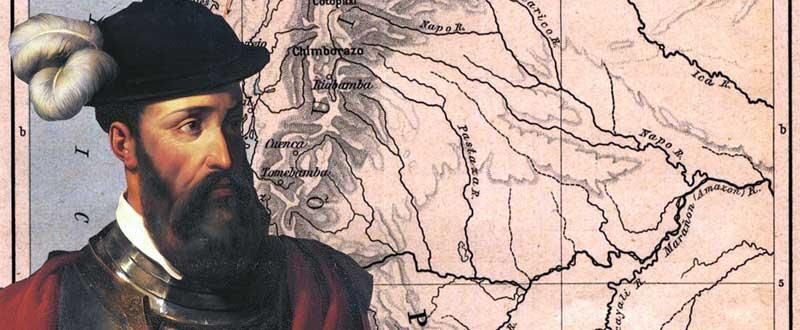

Francisco Pizarro, a peasant from Spain, was one of the least well-equipped conquerors in history. However, in the name of Christ, he destroyed the powerful Empire of the Incas and bestowed on Spain the richest of possessions. Pizarro also established the city of Lima in Peru thus opening the way for Spanish culture to dominate South America.

Francisco Pizarro personifies the greed and heartless inhumanity of the Spanish conquistadors who, in their quest for fame, money and empire, viciously destroyed entire civilizations in the newly discovered lands of the Americas. Some helped rule this gold-rich empire, but many others lived the nomadic lifestyle of the military adventurer - ruthlessly exploiting native populations and extorting the wealth of the land to build vast private fortunes. Pizarro’s place in history is that of the man who destroyed the empire of the Incas and delivered much of the New World into Spanish hands.

Pizarro was born in Trujillo, a small town in the Caceres Province in the southwest of Spain around 1474, the illegitimate son of Gonzola Pizarro and Francisca Gonzalez. His father was a captain in the Spanish military who had fought in the Neapolitan wars. There is little reliable evidence about Pizarro's early life. He is supposed to have been abandoned on the steps of the church of Santa Maria in Trujillo, and there is even a story that he was suckled by a cow. As a youth, Pizarro worked at herding pigs and had no education other than that of a hard upbringing. It is probable that he remained illiterate throughout his life.

Francisco Pizarro came from Estremadura, not only an autonomous community of Spain in the Province of Cáceres but also a region that produced an extraordinarily large number of men who went off to the New World to seek their fortunes and to glorify Spain. The conquistadors' lust for gold was infinite and their religious fervor genuine. Hernan Cortez, the conqueror of the Aztecs, had been born in a nearby town, almost ten years after Pizarro. The wide, infinite skies of Estremadura inspired them with a desire to travel and, combined with the poverty of the land and the news of fabulous discoveries on distant shores, the lure was irresistible.

After the Italian explorer and navigator Christopher Columbus sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain discovered the Americas in 1492, the way was opened to the European exploration and colonization of the unknown territories. However, a year later - to prevent a war between Spain and Portugal over these discoveries in the New World - Pope Alexander VI divided the yet unknown territories into two parts. Using an imaginary 'line of demarcation', the land to the east of the line, which ran north to south several hundred miles west of the Azores and Cape Verdes, now belonged to Portugal, while the land to the west was given to Spain. Almost forty years later, Francisco Pizarro set out for Peru to secure the pagan Kingdom of the Incas for Charles V of Spain and the Catholic Church.

Francisco Pizarro and the Hojeda expedition

In 1509, Pizarro joined the ill-fated Hojeda expedition led by Alonso de Hojeda (also spelled Ojeda), an experienced Spanish explorer, conquistador and governor, that set off intending to colonize the Panama Isthmus. It was to be a grueling time for the inexperienced Pizarro. Left behind in Panama in charge of the new settlement of San Sebastian, Pizarro had to endure near starvation, disease, and poisoned arrows from hostile natives, before the settlement had become so reduced in size that he had no choice but to flee. Using two tiny brigantine ships, Pizarro crammed the sixty surviving men on board. When one sank immediately, he could do nothing but leave the men to their fate and sail away to Cartagena.

Pizarro, Balboa (Panama & Central America)

But luck was on Pizarro's side. Upon arrival in Cartagena, he ran into Martín Fernández de Encisco, a business associate of Hojeda's who had arrived with a relief force of 150 men. They set sail towards Uraba, but Enciso lost his ship on a sandbank. Control of the expedition would have passed to Pizarro, but the emergence of the explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa denied him this opportunity.

Pizarro joined Balboa on an expedition across Panama's infested jungles, and on 29 September 1513 they waded into the waters of the Pacific. It had been the first successful crossing of the Isthmus and was an incredible achievement. On the edges of the Mar del Sur, Pizarro first heard stories of a fabulous golden land to the south and saw pictures of strange new creatures.

The news that Balboa had discovered a new ocean created a sensation in Spain and gave new hope that a route through to the wealthy Spice Islands would soon be found. But Pedro Arias Davila (also spelled "de Avila"), the new Governor of Castilla de Oro, the Central American territories from the Gulf of Urabá, near today's Colombian-Panamanian border, to the Belén River which after the discovery was broadened to include the Pacific coasts of Panama, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua, soon dashed Balboa's dreams of pure exploration. Pedro Arias, who had been appointed Governor because of his court connections, and Balboa hated each other on sight; the small town would not be big enough to hold them both. Within a few months, he had Balboa arrested on charges of conspiracy. Pizarro, who arrested him, had finally got his revenge for being overlooked as the leader of the Uraba expedition. Balboa was executed.

Pizarro, a true opportunist, now quickly transferred his loyalty to Pedro Arias, who sent him to trade with the natives along the Pacific coast. When the capital was transferred to Panama, he helped Pedro Arias to subjugate the warlike tribes of Veraguas, and in 1520 he accompanied Espinosa on his expedition into the territory of Cacique Urraca, in the present Republic of Costa Rica.

By the age of forty-five, Francisco Pizarro had little to show for his many expeditions. His sole assets were some terrible lands and a collection of indigenous people. Accounts of the achievements of Hernan Cortez, and the return of Pascual de Andagoya from his expedition to the southern part of Panama, fired Pizarro with enthusiasm.

All the expeditions, prior to that of Andagoya, had been to the north up as far as Honduras. Few of the newly arrived adventurers were sailors, and the land to the north and west offered safer prospects than the unknown perils of the great South Sea that stretched in unlimited vastness beyond the horizon. Weather made the south a more difficult destination, and the Humboldt current in the Pacific Ocean ensured that the Spanish mariners were faced with tropical storms and violent seas. With no sailing directions, the Spanish learnt by trial and error, and bitter experience.

In Panama, Pizarro formed a partnership with Diego de Almagro, a soldier of fortune, and Hernando de Luque, a Spanish cleric. Their plans were to form a company - the Empresa del Levante - to conquer the lands to the south of Panama. Their project seemed so utterly unattainable that the people of Panama called them the 'company of lunatics'. However, the three were determined: Pizarro would command the expedition, Almagro would provide military and food supplies, and Luque would be in charge of finances and additional provisions. And Pizarro had spent thirteen years in the Indies, and he knew that the biggest prizes went to the boldest and to those who got there first. Luque, a schoolmaster and treasurer of the company's funds, provided the financial backing and with the consent of the governor they began fitting out two small boats for a voyage of discovery.

Pizarro in South America

Pizarro embarked on 14 November 1524, accompanied by 112 Spaniards, a few horses, and a few indigenous servants. He sailed his ship into the Bira River and then continued overland. The going was treacherous, among swamps fringed with dense jungle and vast hills. Finally, Pizarro decided that travel by sea was the lesser of two evils and they returned to the ship. Once on board they were hit by storms, and the food and water ran out. Faced with an increasingly hostile crew, Pizarro allowed those who wished to return to leave for Panama under the auspices of one of his captains, Montenegro.

It was over six weeks before Montenegro returned with provisions. In the meantime, Pizarro and his men had been marooned in the swamps of Puerto de la Hambre (Port of Famine), where they had been reduced to eating shellfish and seaweed on the shore and whatever sustenance they could gain from the fetid land. But all was not lost. Pizarro had contacted the natives and listened to stories of a powerful kingdom to the south. He also had his first look at some gold ornaments, and it whetted his appetite.

They headed south again, hugging the coast, determined to push their luck to the very edge of disaster, but all they found were deserted villages, a little maize and more crude gold objects. In desperation, Pizarro marched inland, but was attacked by indigenous people in the foothills of the Cordilleras Mountains. It was a bloody engagement and Pizarro was wounded; however, the native were finally repulsed.

Pizarro and his crew had travelled only as far as Punta Quemada, on the coast of modern-day Columbia. Once back on board, they fled back to the Pearl Island archipelago in Panama. They finally met up with Almagro's ship at Chicama, and Pizarro discovered that Almagro had only made it a little further up the coast before being forced to return. However, the adventurers would not give up so easily. Almagro and Luque returned to Panama to meet with the governor. Pizarro, who hated bureaucracy, was extremely conscious of his lack of education and sent his treasurer, Nicholas de Rivera, to get money and supplies for a new expedition.

Pizarro’s Expedition in 1526

A second request to Pedro Arias for permission to recruit volunteers for a new expedition was met with hostility. Their first voyage had lost money and Pedro Arias was already organizing an expedition to Nicaragua. But luck was with them again and with a new Governor, Don Pedro de los Rios, and the persuasions of Luque, the funds were raised. Pizarro and Almagro were made joint leaders of the new expedition and on 10 March 1526, a contract was signed between Pizarro, Almagro and Luque. They agreed to split all conquered territory and any gold, silver, and precious stones three ways, less the one-fifth required by Charles V, King of Spain.

They purchased two ships and Pizarro and Almagro directed their course to the mouth of the Colombian San Juan River. Pizarro set off with a group of soldiers to explore the mainland, capturing some natives and collecting gold. Upon his return, the two ships separated; Almagro went back to Panama to get reenlistments and sell the gold; and the other ship, under the command of Bartolomé Ruiz, Pizarros's "main pilot" (piloto mayor) set sail for the south. Ruiz got as far as Punta de Pasados, half a degree south of the equator. After making observations, collecting information and capturing a balsa (raft) with natives from Tumbes, today a city in northwestern Peru. on board, he returned to Pizarro. In the meantime, Pizarro had ventured inland once more, but to no avail. All they had found was impenetrable rainforest and deep ravines. He had struggled back to the coast, near to starvation, to await the return of his partners. After seventy days, Ruiz returned with just the news they had been waiting for. He was full of tales of an increasingly populated and friendly land, overflowing with riches. And he had two "Peruvians" on board to verify the stories.

Shortly after, Almagro returned from Panama with eighty newly arrived recruits from Spain. With full bellies and more men, the two ships sailed on to Atacames on the Ecuadorian coast, on the edge of the mighty Inca Empire. Set upon by hostile natives, the adventurers had no option but to retreat. After a bitter row, Pizarro agreed to remain behind whilst Almagro returned to Panama to sell the gold they had found and drum up more reinforcements.

Pizarro camped on the island of Gallo, a barren place. Living an unhappy existence on the desolate island, it was not long before Pizarro's men became mutinous. When Almagro's ship departed, they sent a note concealed in a bale of cotton, implying that Pizarro was holding them against their will. When the note came to the governor's attention, any chance that Almagro had of maintaining the governor's support ended, and two ships were dispatched to bring Pizarro back.

When the ships reached Gallo, they found the men in a state of near-starvation. Those that were left had been drenched by tropical rains, their clothes were in rags and their bodies, having been scorched by the sun, were covered in sores. Almagro and Luque had sent letters imploring Pizarro not to return nor give up all they had worked for, and so Pizarro, in true conquistador fashion, stayed and ignored the governor's command. Drawing a line in the sand he summoned the remaining men, saying, 'Gentlemen, this line represents toil, hunger, thirst, weariness, sickness and all other vicissitudes that our undertaking will involve. There lies Peru with all its riches; here, Panama and its poverty. Choose each man, what best becomes a brave Castilian. For my part I go to the South.' Then he stepped over the line — thirteen remained with him, one of whom was his navigator, Ruiz.

The forlorn, abandoned men stood and watched as the two ships set sail for Panama and disappeared over the horizon. All was not lost, however, as Almagro and Luque could persuade the governor to give them and Pizarro another chance. Reluctantly the governor agreed to back them and one ship, with no soldiers, was provided with the stipulation that they had six months before they had to return. It had taken months to get consent from the governor, but Pizarro had learnt from previous experience and during this time had organized the building of rafts and moved to the island of Gorgona, seventy-five miles up the coast. This beautiful island was stocked with fresh water and virgin forests, and by the time the governor's ship found them, Pizarro and his followers were in good spirits.

Francisco Pizarro arriving in Peru

Leaving Gorgona behind, the ship now sailed south, crossed the equator, and arrived in the Bay of Tumbes. On the land they could see towers and temples rising above the green fields. They had arrived in the Empire of the Incas.

The following morning, a fleet of rafts with Inca warriors came out to investigate the mysterious new arrivals. Pizarro invited them on board and asked his two Peruvian crew members to show them around. One of the Inca soldiers was a member of the government, and he invited Pizarro to visit the city. He returned from the city with tales of a temple, tapestried with plates of gold and silver, and information on the city's defenses. With only a few men, Pizarro could not take what he wanted, but vowed to return later.

For now, however, it was time to turn back, time to raise an army, to shed the cloak of discoverer, and assume the armor of conqueror. Pizarro had discovered Peru; the next thing he intended to do was to take it.

Pizarro preparing his conquest of Peru

Tales of the Sun God King would be enough to set Panama ablaze with excitement, or so Pizarro believed. On his return, after eighteen months away, Pizarro was feted; everyone marveled at his achievements, but the full-scale expedition that he was proposing was deemed beyond the colony's capacity. The governor was not a conquistador so Luque proposed that they petition the Crown of Spain directly and Pizarro, full of his newfound confidence, left for Spain.

Immediately after Pizarro arrived, he was jailed as punishment for an old debt, but fortunately, tales of his exploits had reached the court, and hungry for more money from the New World, they released Pizarro. They brought him to Toledo to meet with King Charles V, and after securing the King's blessing, Pizarro now had to deal with the Council of the Indies — a bureaucratic machine that had grown fat on the exploits of others.

Finally, on 26 July 1529, in the absence of the King, Queen Isabel signed the Capitulación de Toledo, allowing Pizarro to proceed with the conquest of Peru. Pizarro was officially named the Governor, Captain-General, Adelantado and Alguacil Mayor of New Castile for life and granted a large salary. They made Luque Bishop of Tumbes as well as 'Protector' of all the natives of Peru, and Ruiz became Grand Pilot of the Southern Ocean with a salary to match. Almagro got virtually nothing; Pizarro had betrayed him on the premise that Almagro had not been present on the voyage of discovery.

Pizarro’s conquest of Peru

But Pizarro's troubles were far from over. Although the crown had granted him a title, they expected the expedition to be self-financing, and money still had to be found. Spain might reap the rewards, but they were not prepared to take a risk financially. Elated by his success, however, Pizarro returned to his home in Trujillo to get more men. His brothers Gonzalo, Juan and Hernando joined him on the adventure. Hernando, a terribly cruel man, was to become Pizarro's right-hand man. It took a further six months to raise the money and fit out the ships. Finally, they left for Panama in January 1531 and sailed to Nombre de Dios to meet with Almagro. On arrival, Pizarro clashed with Almagro immediately, not helped by Hernando, who was openly scornful of the old man. Eventually peace was restored, but from the start the three chief personalities were at odds.

With extraordinary arrogance and pride, the fifty-five-year-old Pizarro was now embarking on his voyage of conquest. He had three vessels, two large and one small, 180 men, 27 horses, arms, ammunition, and stores. With these supplies he intended to conquer an empire that was home to about 12 million people at the time and stretched over 4000 km (about 2500 miles) from the border of Ecuador and Colombia to south of modern Santiago, Chile and included one of the world's greatest mountain chains and extended inland to the rainforests of the Amazon.

Initially, the forces of nature halted the invaders in San Mateo Bay, 350 miles away from Tumbes. Pizarro then put his men on shore and march them south. His men looted and sacked a small, undefended town. It was the height of stupidity, because for just a small immediate financial gain, Pizarro had lost not only any hope of achieving surprise but also the goodwill of the natives. Incarcerated in their quilted cotton clothing and heavy armour, his men became victims of the tortuous heat, and many died. It was the most senseless start to a campaign that any general could have conceived.

Eventually they arrived at the island of Puna, having been joined by two more ships carrying the Royal Treasurer and administration officials. Pizarro then started a war between the Puna and the Tumbes (the Puna's mortal enemies), and the Spanish were forced to seek refuge in the forest. Evacuation became a necessity and with more volunteers and horses, Pizarro returned to Tumbes on the mainland. But Tumbes was not the town anymore he set food on a few years earlier; it was just a shell of its former glory. Initially furious and disheartened, Pizarro ranted and raved. But his phenomenal luck had not deserted him. Unbeknown to the Spanish, they had chosen the ideal time for an invasion of Peru. The Inca Empire was in the middle of a bloody civil war.

The Inca reign started around the 11th or 12th century after Manco Capac, the founder of the Inca civilization and first Sapa Inca (the ruler of the Kingdom of Cuzco and later, the Emperor of the Inca Empire), had made Cuzco his capital, however first remained limited to the Cusco region. Following Sapa Incas expanded as far as Lake Titicaca, Arequipa and the Andean highlands of Ayacucho and Abancay. Later, beginning in the late 14th century Pachacutec - fourth Sapa Inca of the second dynasty - transformed the Kingdom of Cuzco into the vast Inca Empire of Tawantinsuyu.. By 1493, just thirty years before Pizarro's arrival, they had conquered the whole of Peru, parts of Bolivia and Ecuador and most of Chile — an area of about 380,000 square miles. The Inca armies contained 300,000 troops.

Pizarro and the Sun God Atahualpa

However, in 1524 - the year that Pizarro had first landed in Tumbes - Huayna Capac, the sixth Sapa Inca of the second dynasty and eleventh of the Inca civilization, was near death. Instead of giving the control of the vast Inca Empire to his son and legitimate heir Huascar, he split the Empire between Huascar and his favorite son Atahualpa. Atahualpa was given control of the north centered in Quito, while Huascar was given the southern area of the Empire centered in Cuzco. For the next 5 years the two brothers reigned in tense peace as Huascar saw Atahualpa as the greatest threat to his power, but respecting his late father's wishes didn't dethrone him. Instead, he got support from native tribes dominating extensive territories of the north of the empire and maintained grudges against Atahualpa. However, in 1529 Huascar had enough and sent an army to the north, ambushing Atahualpa in Tumebamba and defeating him. Huascar had Atahualpa arrested, who could escape imprisonment and with support from his late father's best generals and a great army now marched against his brother. A bloody, ruthless and atrocious 3-year civil war erupted which killed thousands and left blossoming cities, the infrastructure and strict organization as well as large parts of the great Inca Empire in ruins. In the ultimate battle between the two brothers - the Battle of Quipaipán near Cuzco - Atahualpa's army once again was victorious. Huascar was captured, he and his family killed and Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire seized.

With the Inca Empire weakened, Pizarro knew that now is his chance to go for the total conquest of the vast Inca nation. After having occupied Tumbes and having founded the City of San Miguel de Piura (today's Piura) he set off into the interior with a small force to win over the local population and to turn his men into a disciplined fighting machine. Any resistance from the natives was brutally eliminated and soon entire regions were under his control.

Pizarro now had 110 foot soldiers and 67 horse troops, of which only 20 were armed. Should he march further or wait for reinforcements? He pondered his dilemma, aware that Atahualpa had over 40,000 warriors at his command. Finally in September 1532, Pizarro marched.

Atahualpa, who stayed in Cajamarca after the successful conclusion of his northern campaigns and before returning to Cusco, had been aware of the Spanish progress right from the start, but was unsure what to make of the visitors to his kingdom. He had received reports of the Spanish ships, their guns and firearms and how the Spanish rode animals much larger than the Peruvian lama. So, being curious, he sent an Inca noble to investigate the Spaniards and after returning with an assessment Atahualpa decided Pizarro and his men were no threat to him and his 40.000 soldiers. So first he waited with his army, letting the Spanish approach him unmolested. He was like a child, mesmerized into inactivity by his curiosity and presumptuousness. By mid-November 1532, Pizarro's tiny force was descending the Andes into Cajamarca. Atahualpa invited the Spaniards to set camp in the city and meet him, expecting to capture them.

Once in the relative safety of Cajamarca, Pizarro sent a delegation of twenty horsemen to arrange a meeting with Atahualpa who camped with his army on a hill just outside Cajamarca. It was doubtless a daunting sight for Pizarro's small band of adventurers as they rode into the heart of the great Inca army. Atahualpa greeted them wearing a collar of enormous emeralds; his whole cavalcade blazing with gold. The Spanish caballeros in their armor also made a deep impression, and Atahualpa agreed to meet with Pizarro the following day.

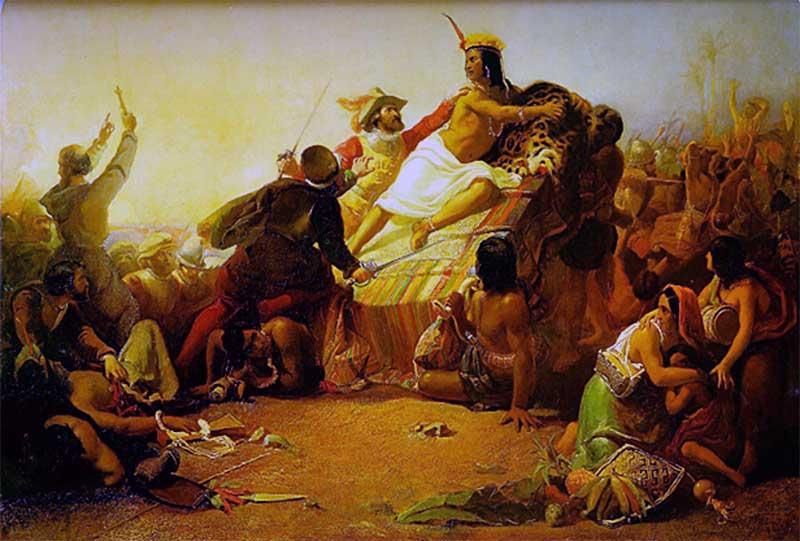

Meanwhile, tensions were building in the Spanish camp and even the arrogant Pizarro would have been aware of just what they were risking, and prepared an ambush to trap the Inca. He first wrote to Atahualpa, implying that the Inca king lacked the courage of true nobility. In his desire to show bravery and with his two most trusted generals, Quizquiz and Challcuchima, fighting in Cusco, Atahualpa set off to meet Pizarro with only 6,000 unarmed warriors. Before the arrival of Atahualpa in the city, the Spaniards however "prepared" Cajamarca. The Spanish cavalry and infantry were occupying three buildings around the main plaza, and some musketeers and four pieces of artillery were located in a stone structure in the middle of the square. The plan was to persuade Atahualpa to submit to the authority of the Spaniards and, if this failed, either a surprise attack, if success seemed possible, or keeping up a friendly stance if the Inca forces appeared too powerful.

When Atahualpa arrived at Cajamarca the next day with his men, he found - contrary to his expectations and entitlement as Sapa Inca - the main square empty. The only one appearing was the Dominican friar Vincente de Valverde with an interpreter who invited Atahualpa to come inside one of the buildings to talk and dine with Pizarro. Atahualpa didn't follow the invitation, but demanded the return of everything the Spaniards had taken since they landed. The priest, however, thrust a Bible into Atahulpa's hand and urged him to renounce his own divinity in favour of Jesus and acknowledge Charles V as a king greater than himself. Atahulpa exploded with anger as he threw the Bible to the ground. Suddenly Pizarro gave the signal, and the guns and cannon boomed out across the square as the Spanish troops poured in, their swords flashing in the afternoon sun. The steel soon turned crimson as they hacked away at the surprised, unarmed soldiers of Atahualpa's army. The Peruvians died fighting with their bare hands in defence of Atahulpa. The attendants and some of the unarmed Incas broke down a wall and fled into the countryside, pursued by the cavalry. The butchery of those that remained trapped in the square did not stop until it was almost dark. Such was the blood lust of the Spaniards that it was only the intervention of Pizarro himself that saved the Inca king, who was imprisoned immediately.

By capturing the Sun God, Pizarro had virtually immobilized the entire Inca army. The soldiers eventually melted away into the surrounding countryside and no attempt was made to rescue Atahulpa. On November 17, 1532, the Spanish sacked the Inca camp where they found 5,000 women, who they promptly defiled, and a great treasure of gold, silver and emeralds. One gold vase weighed over 100 kilograms. It was unbelievable. Pizarro suddenly found the great empire wide open, and it had all been achieved by a stroke in which not a single Spaniard lost his life. Indeed, none had even been wounded, except for Pizarro himself, who had received a sword cut whilst defending Atahulpa from the blood lust of his own men.

The betrayal and death of Atahualpa

Mysteriously, Atahualpa did not try to contact his generals, and when he saw the Spanish lust for gold, he made Pizarro an offer he could not refuse. He proposed that, in exchange for his life - some say his freedom - one of the immense halls in Cajamarca be filled with gold. But to make sure that the terms of ransom would never be met, Pizarro insisted that additionally another room would be filled twice over with silver. Atahualpa had bought time and probably still believed that he could escape, but did not seem to doubt Pizarro's word of honor.

As several weeks passed, tension mounted in the Spanish camp before the treasures trickled in. The carriers had vast distances to overcome, and the treasure pile grew slowly. Pizarro even dispatched three of his men to oversee the dismantling of the great Temple of the Sun. The men were treated like gods but behaved appallingly, even dishonoring the sacred Inca Virgins of the Sun. Rumors abounded in Cajamarca of an attack and Pizarro sent his brother, Hernando, and some men to investigate. By February 1533 Almagro and reinforcements joined Pizarro. Pizarro wanted to move on.

By now the treasure amassed stood at 1,326,539 gold pesos and the rooms were still not filled. Pizarro decided that he had waited long enough and that the spoils should be divided. Hernando was dispatched to Spain to report to the Emperor and give him his share.

Meanwhile, the mood in the camp was rapidly building up to where the men themselves would demand what Pizarro wanted most - to get rid of Atahualpa. The Inca king had now become a nuisance. He had served his purpose. Pizarro had the gold: now he wanted power. An empire was within his grasp, but if the Inca king lived, he provided a rallying point for resistance. His death had become a political and tactical necessity.

To make Atahualpa's death appear just and legal, Pizarro set up a court, with himself and Almagro as the judges, and tried the defeated Inca king. They accused Atahualpa of twelve crimes, including adultery, because he had many wives, and worshipping idols. Pizarro had turned Inquisitor in his new Empire. The trial was a farce, and they sentenced Atahualpa to be burned to death. On July 16, 1533, he was carried by torchlight and placed on the stake. Some of Pizarro's generals protested, but eventually agreed on the grounds of expediency.

Peru, after the death of Atahualpa

Now the Spaniards were free to march on to Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire. Throughout the months they had stayed at Cajamarca they had been living off the accumulated wealth of the indigenous people, slaughtering around 150 lamas a day as though there was no end to the flocks of these animals, plundering the supplies, and demanding and receiving a steady supply of food from local chiefs. They were men without thought to the future, and the curse they carried with them was the curse of their own greed. They now embarked on the destruction of the whole brilliant civilization without possessing the organization to replace it.

On November 15. 1533, one year after arriving in Cajamarca, the Spanish entered Cusco and gained control of the capital of the Inca Empire. On the march, the Spanish had collected a further half-a-million gold pesos of treasures. Other Spanish troops now joined Pizarro, eager to share in the wealth of the conquered Inca empire. By now Pizarro was the absolute master of Peru - and would remain so for eight years. Had he had any real administrative ability, he could have had the cooperation of the entire nation. The Peruvians were a stoic race, accustomed to passive subservience rather than active loyalty to a central Inca government. But Pizarro and his soldiers mistook passivity for cowardice, and they indulged in the worst excesses towards the population. Increasing attacks, riots and rebellion of the remaining Incas were bloodily suppressed, and the Incas retreated to the nearby mountains.

The Foundation of Lima

In 1534 Pizarro left Cusco high in the Andean mountains looking for a suitable place to establish "his" city. In the desert stripe between the Pacific Ocean and the Andes in the fertile valley of the Rimac River (and two other rivers nearby that provided fresh water) he found the place he was looking for.

People had been living here for thousands of years and developed the countryside into green oases with extensive fields and fruit plantations. The location offered easy access to coastal fishing grounds, a good infrastructure and it was close to the natural harbor of Callao. What was soon known as the "City of Kings" or just "Lima", was on New Year 1535 still home to about 150,000 indigenous people in a region called Cuismanco and governed by Taulichusco.

On January 18,1535 Pizarro founded Lima on the territories and temples of the leader Taulichusco next to the Rimac River. "Pizarro's Palace", later subsequently called "Palace of the Viceroys of Peru" and today the Presidential Palace was built on the site of Taulichusco's home. The Cathedral of Lima was built on the grounds of a religious temple. For better or worse, the founding of Lima marked the beginning of a new chapter in Peru's history.

At the beginning, Lima only accommodated a dozen conquerors. Pizarro himself based the design and layout of Limas city center on the model of cities in Spain (especially Seville). The first 'mansions' simple houses with reed roofs, were all built cuadra by cuadra (block by block) around the newly established main square, the Plaza Mayor, in a chessboard style and with specific rules (exact length of one block = 400 feet/122 m and a precise width of the streets = 40 foot/12.2 m). The indigenous population was forced to slavery labor, building the capital.

While Pizarro was building Lima, the new capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, Almagro was governing Cusco, having been made independent of Pizarro by King Charles. Unfortunately, in dividing up their areas of control, the King of Spain had been extremely vague, and both Pizarro and Almagro claimed Cusco for their own. This struggle for power resulted not only in splitting up Cusco into fractions and later its near complete destruction, but in the end as well in a long, bloody and brutal civil war between Francisco and his brother Hernando Pizarro and Diego de Almagro including their followers; and some Incas rebelling against the Spanish rule were involved as well. The entire country seemed to be in revolt and even the newly established capital, Lima, wasn't spared.

In 1538, after once again tricking Almagro, Francisco Pizarro gathered his forces and attacked Almagro. In the Battle of Las Salinas over 150 Spanish died, his old ally Almagro was defeated, captured by Hernando Pizarro and executed.

Pizarro now settled down to administering his great kingdom and organized a series of expeditions to discover unknown lands, but while his brother Gonzalo was staggering out of the steaming forests of the Amazon, the fortunes of the Pizarro family were reaching their inevitable climax.

The death of Francisco Pizarro

Discontent was rife throughout the country. More and more Spanish were flooding in every week, and Almagro's son, Diego de Almagro II, together with a group of followers, swore revenge on Pizarro. On June 26, 1541, Pizarro was told of a plot against him, but he took brief notice of it. However, around midday a group of 20 heavily armed conspirators entered the Governor's palace and assassinated Pizarro, plunging their swords repeatedly into his body.

Francisco Pizarro, the peasant's son from Spain, was dead and with his death the era of the conquistadors was drawing to a close. In just over half a century, a whole new world had been opened up. But the conquistadors were fighting men - the consolidation of the empire they had taken was left to others. The once mighty Inca Empire with its political structure, infrastructure, beliefs, customs, traditions and enormous treasures was destroyed and soon flooded with swarms of Spanish officials, taking over and implementing the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Pizarro died as he had lived. His readiness to kill in pursuit of wealth and power was the defining feature of his career. In the process he destroyed an ancient culture and opened the South American continent to centuries of European exploitation: indeed, the crimes of the Spaniards who came in his wake arguably outweigh those of the man himself. Many Peruvians today regard him not as a hero, but as a criminal guilty of genocide.